Recently, I have finished listening to “The Lean Startup” by Eric Ries, an engineer and entrepreneur. His fist-handed experience of founding and working in startups led him to the creation of guiding rules for startup success. The book is full of descriptive examples from Eric’s own experience as well as from the product teams he consulted. Most of the crafted principles are supported by facts and figures and sounds fairly reasonable – a mature vision that should be taken into consideration. So, here are just a few insights from the book I personally found noteworthy.

Moving Fast but in the Wrong Direction

“No wind blows in favor of a ship without direction.”

― Seneca the Younger

It doesn’t matter how cool is your new shiny product or its feature, if it doesn’t contribute to your bottom line. You can be creating an ultimate solution for some problem, or at least thinking so, and delivering new features really fast like deploying to production dozens of times a day and still fail. The most common reason for such failures is the lack of feedback from your customers and/or inappropriate metrics for your business success.

In the first case, you might postpone monitoring end-user experience and collecting telemetry data until launching your app or service into production. Why? Because real developers build things, and this is Ops who shall run and monitor them (sarcasm). For example, a recent case from my work activity involved troubleshooting the computer system that didn’t have sufficient monitoring configured. Intentional performance optimization in one system component caused a bottleneck in its dependency, and the whole system went off—a good intention with a bad outcome.

Secondly, as an old expression says, “you get what you measure.” If you keep an eye on application and infrastructure metrics only, you are highly likely to overlook the impact of your work on the business metrics that are crucial for your venture. If you cannot identify the most relevant figures for the current state of your business and if you cannot connect the dots to get their values from your development process, you are doomed to sailing as a ship without direction.

Test, Fail, Repeat, Succeed

“Everything is a test.”

― Terry Pratchett, I Shall Wear Midnight

Countless examples of false assumptions in the high-tech industry proved that all theories should be tested in practice. In his book, Eric Ries also mentions a few cases when the ideas promoted by recognized industry experts turned out to be completely wrong. For example, a product team might think that implementing feature X is what their customers desire. Upon delivering that feature to the customers, feature acceptance metrics show that the feature is completely ignored and not used. Is it failure or success?

On the one hand, you might think about the work effort required to build such a useless feature as a complete waste of time. From the traditional business perspective, the feature ROI is zero, and the capital invested in it is a loss. Sounds not very appealing, right?

On the other hand, it is the nature of a startup, a venture in a new business area, to be a game of high risk, high reward. Basically, when you explore new business opportunities, you a very likely to fail multiple times before you find your product-market fit. If you understand why your product/feature test failed, you can and should use that knowledge to your advantage when planning your next series of controlled experiments. That is how the scientific method works – you make a hypothesis, test it, and then use obtained data to make your next guess. If organizing your development process around conducting deliberate tests, you can gain value from each investment of time and effort and progress further in your exploration. The author named that phenomena ‘validated learning.’

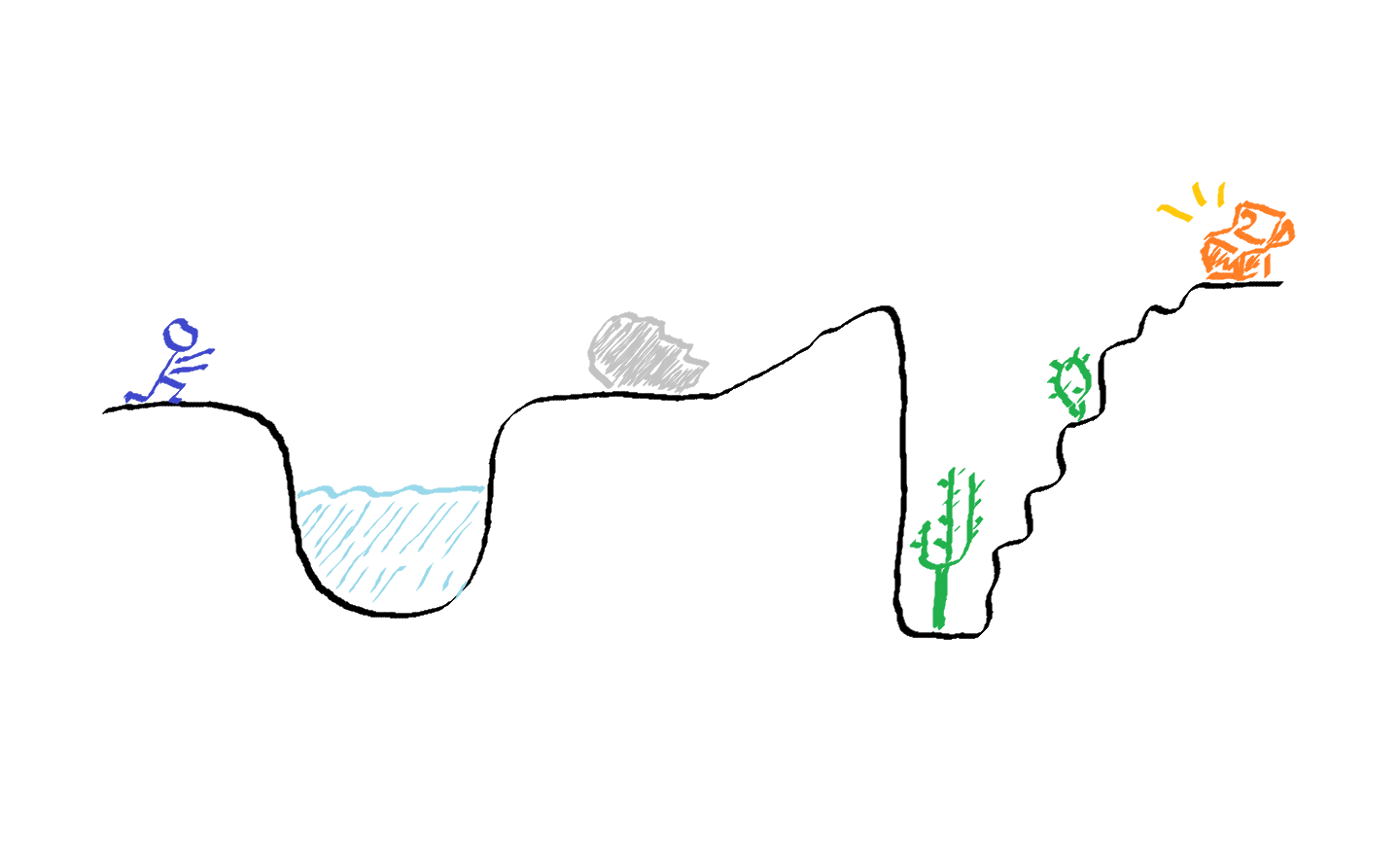

Besides the constant learning from your development process, the applied methods itself should minimize the waste of time and resources. The most common caveat is that the delivery cycle is either too long or too short.

In the former case, after weeks or even months spent on implementing new functionality, you might realize that you took the wrong path and added no real value to the product/service. As a result, the experimentation cost is too high, and the time you might have spent on more promising assumptions is irretrievably lost.

In the latter, you might disregard quality and functionality for the sake of speed to such extent that the delivered features are buggy, incomplete, and cause more trouble than order. Consequently, your product/service might gain a bad reputation as being not worth any attention.

In both cases, the extremes in the development cycle are equally harmful, and there is no one-size-fits-all. The cycle duration should be validated in practice as any other belief.

Speed or Quality?

“…with fronts of brass, and feet of clay.”

― Lord Byron, Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte

The idea of the minimum viable product (MVP) popularized by the author and the Lean Startup movement attracted lots of attention and is being explored now by many product teams. At the same time, an MVP, also known as the first or pilot version of the product, is often very different from a product that is ready for mass consumption.

For the sake of development speed, an MVP can be a monolithic application or tightly coupled service that lacks many essential features available in similar solutions. It might not perform acceptably at scale, be of poor technological design and a splitting headache in terms of supporting it. I would compare an MVP with a concept car: you can see it, like it, and probably wish to buy it, but you cannot drive it right away. As with a concept car, an MVP has to undergo many changes before being a production-ready solution.

If your MVP proved to be valuable to your target audience of early adopters and you are planning to go mass-market, it would be wise to change your priority from developing new features to polishing the existing ones and investing more effort in product/service quality. What if forgivable to an early access version is completely unacceptable in a paid product.

Apart from that, if a startup team starts spending more time on fixing bugs rather than delivering business value, you are heading towards nothing but trouble. It might be a high time to rebuild or even to design a completely new version of the product/service that should address existing quality, stability, and scalability issues. Otherwise, you might end up building a colossus with feet of clay.

Disruptor Innovator vs. Rigorous Administrator

“Those good at war aren’t good at peace, and those good at peace aren’t good at war.”

— Winston Churchill

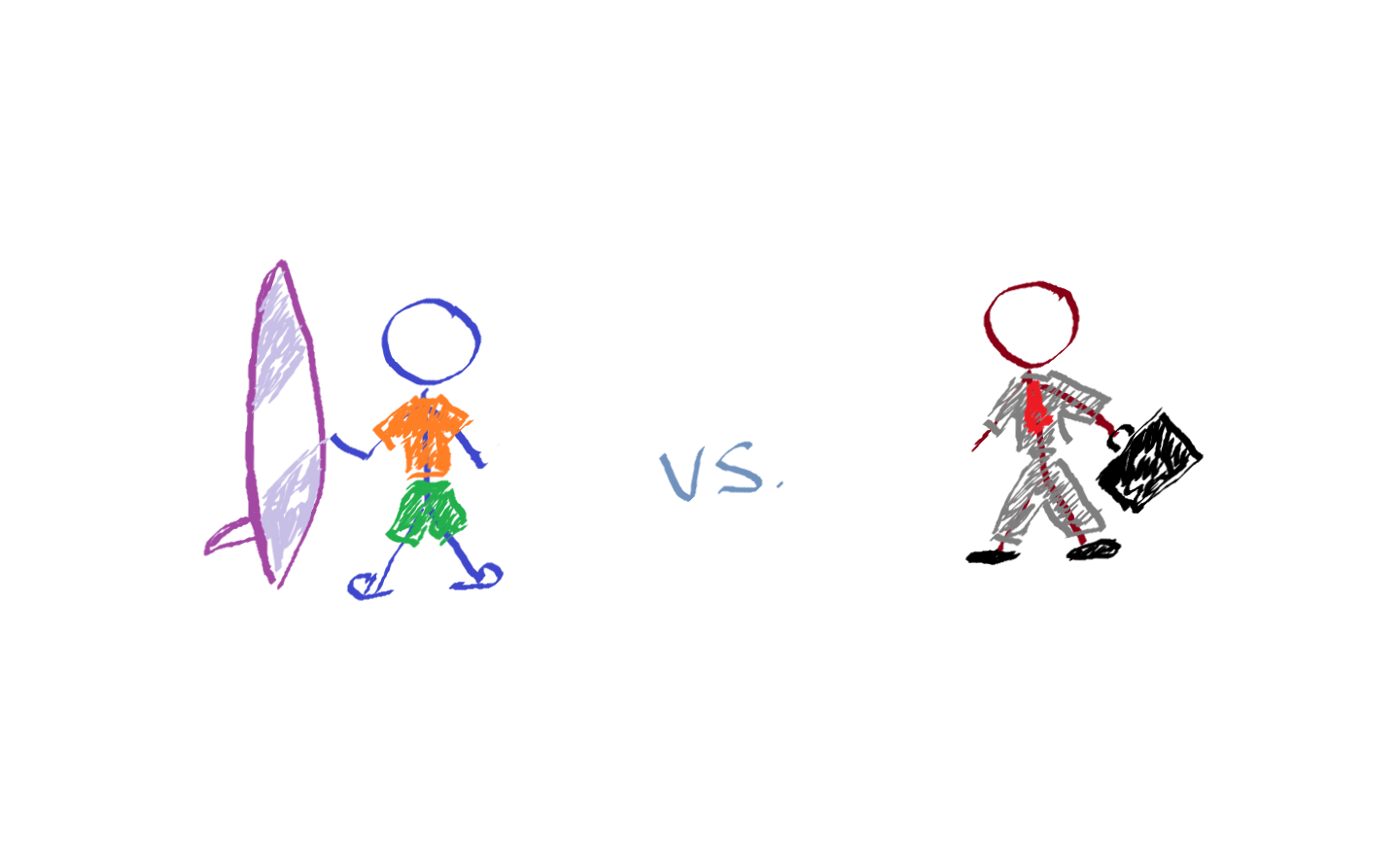

During his startup consultancy, Eric Ries noticed that a person who starts a venture, aka founder CEO, usually is not so good at running the business at later stages – when a market fit is achieved, things settled down, and it’s time to focus on steady growth. Of course, there are exceptions, and many founders like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, and others have continued to steer their companies when they become full-fledged enterprises. Still, in many cases, founder executives prefer to sell their established businesses or to step down and entrust running it to a hired professional CEO. Often, during that transition process, such founder ex-CEOs also launch a new startup or start exploring new business opportunities.

A similar idea was expressed by Ben Horowitz, a founder of Opsware, in his book “The Hard Thing About Hard Things.” He contrasted two types of executives – a war-time CEO and a peace-time CEO. Only in rare cases, the same person can execute with the same level of effectiveness during the periods of both crisis and prosperity.

The observed pattern explains that a person starting a new business is generally willing to act in an environment of high uncertainty – such people like competition, innovation, and dream big ideas. For them, doing a routine, day-to-day administrative work looks like the hell they are trying to escape at any cost. Dr. Ichak Kalderon Adizes, in his book “The Ideal Executive,” provides a character model (PAEI) that distinguishes four core personality traits: producer, administrator, entrepreneur, integrator. According to the model, entrepreneurs are usually people who have developed producer and entrepreneur skills. In other words, they are rather result- than process-oriented, and focus more on a big picture than on details. Doing administrative work or managing people are not the areas of their inspiration.

During the early days, a business requires more charismatic and inspirational leadership, a la ‘pirate captain’ style. With enterprise maturity, process establishment and people relations tend to become more important for a person ‘in charge.’

The thoughts I noted down in this post are just a fraction of a much broader set of ideas of the Lean Startup movement. To get the full picture and to make your judgment about this book, I encourage you to grab your copy and enjoy the reading!

|

Member discussion: