To my mind, this book can provide you with a fresh look at what might be of more importance than any existing methodology for an enterprise to succeed. Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais raise a few essential questions about the influence of Conway’s law on organizations’ performance and operational excellence. A significant part of the book is also dedicated to the psychological aspects of interhuman communication and cognitive load, which play a vital role in the teamwork processes.

To make the book even more appealing to a thoughtful reader, most of its ideas are supported by both research data and real-life examples. The experience of many organizations described in the book can give valuable insights into what proved to be efficient and what was not.

There are already enough summaries for “Team Topologies” on the web, and I’m not going into retelling the book content here. Nevertheless, it might be useful to compare the topologies with already established IT team patterns to understand the underlying book ideas better.

Four team patterns

Some people I discussed this book with wondered why the authors limited the list of team topologies to four patterns only. I see two reasons for that. The first one is that the authors suggest those specific team topologies because of their interaction modes: each topology has preferred ways of external communication that maximize its cooperation with counterparts. Secondly, keeping the variation of team patterns to the bare minimum that satisfies 80 percent of common organizational cases makes the solution with four building blocks much more manageable than with forty ones. So, let’s start with the first topology.

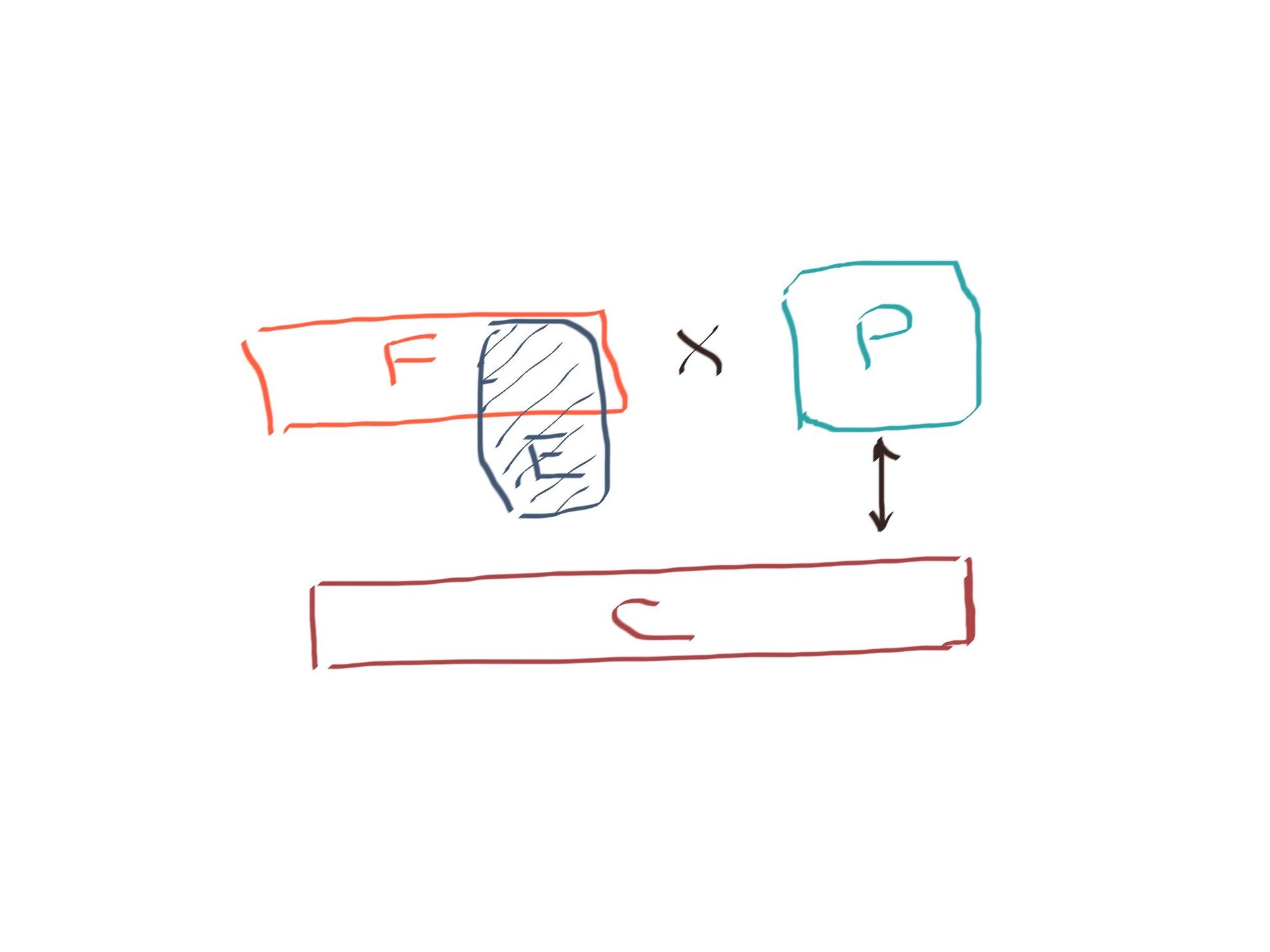

A stream-aligned team is optimized for speed and efficiency. Of course, each optimization comes for a price, and, in this case, you pay for it with reduced flexibility. You can compare such a team with a conveyer – it’s very efficient but in doing one and one thing only. If you need that team to perform something different, it might take quite a while to reconfigure its flow to produce new results.

Often, stream-aligned teams are confused with functional teams like network, security, or DBAs. However, traditional functional teams, especially in siloed organizations, are usually responsible for many different activities in quite broad areas. For example, a classical functional team might be accountable not for service operation only but also for running implementation projects, designing new solutions, and consultancy for other teams. That can hardly be considered a single stream of value. Even the term’ functional team’ is misguiding as such a team rather represents a specific area of expertise in an organization than an atomic function.

An enabling team is what drives innovation and help other teams to optimize their work. It’s like a gang of skilled techies who are experienced and, at the same time, striving for new knowledge and improvement. These men and women consult, train, and introduce improvements to help other team types do a better job. A common example of this team type is a center of excellence in an organization.

The typical faults of enabling teams are mostly related to unbalanced duties. On one extreme, they might degrade to purely educational functions – doing only training and explaining cold theory with no significant impact on other teams’ well-being. On the other, when getting too involved and doing someone else job, a team initially intended as enabling will soon transform into another functional team: supporting the tools it promotes, running operations, leasing its resource left and right, and getting bogged down with rising demands from other teams.

A complicated-subsystem team encapsulates some complex technology or knowledge domain to ease its usage by other groups. This team pattern makes sense when it is hard or too expensive to acquire that knowledge in all teams that have to use the subsystem.

The closest analogy for the complicate-subsystem team that I can come up with is tier-3 support. However, most tier-3 teams are cross-functional and address complex issues at the top levels of organizations. On the contrary, the core idea of complicated-subsystem teams is that they should be limited to one complex domain to benefit from Conway’s law.

The platform teams’ primary objective is to provide other teams with tools and services they can use autonomously with minimal interaction with the provider. For example, such a team can provide an in-house deployment service that other teams in the organization use to deploy their applications.

A product team that builds and supports applications to be used outside can be considered as a platform team. However, in large and complex solutions, the product team itself might consist of multiple internal sub-teams responsible for different parts of the product lifecycle: development, support, operation, etc. The rule of thumb here is to compare the teams of equal scale.

The myth of cross-functional teams

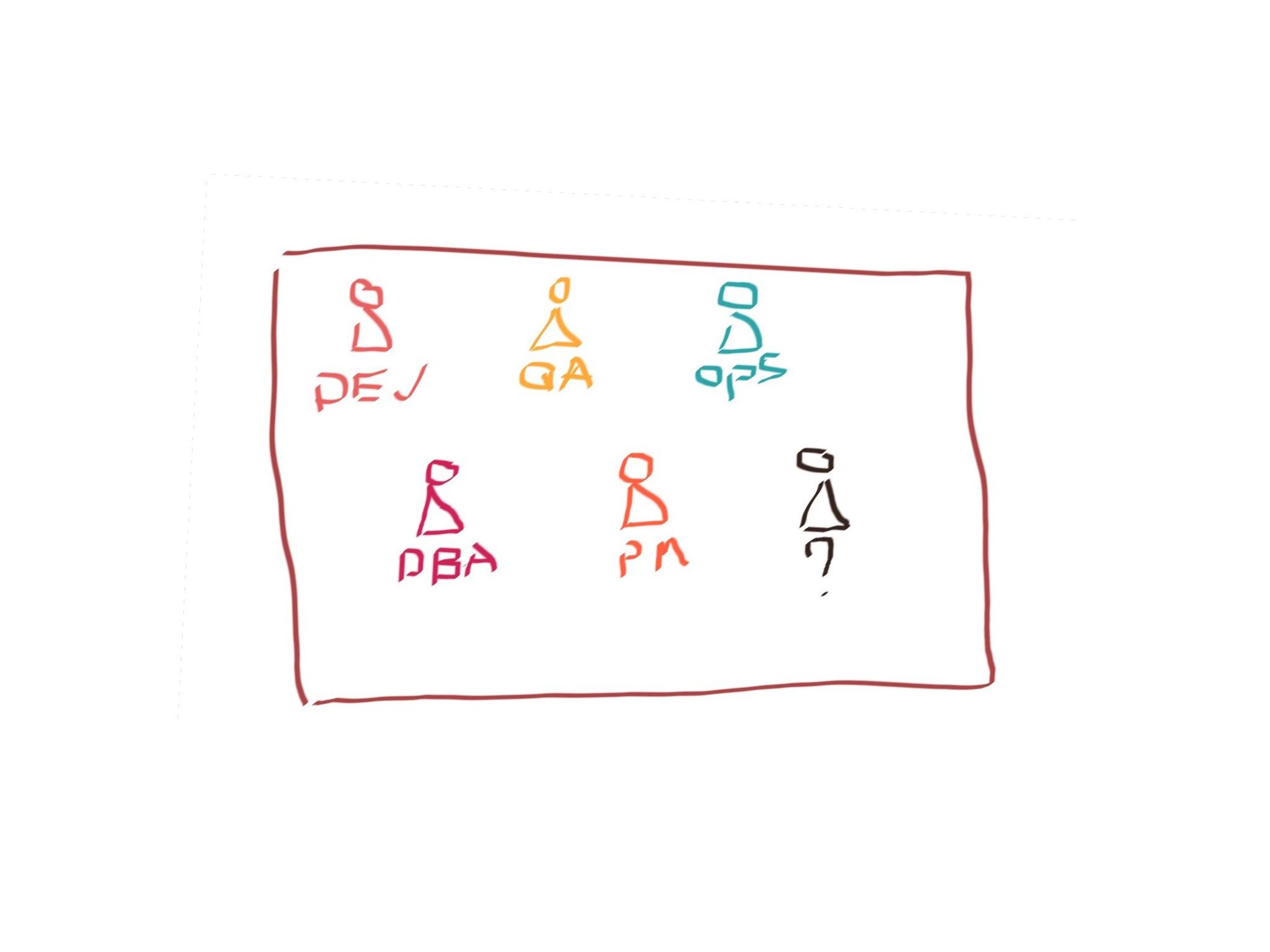

In the era of DevOps being a hot topic, you might wonder how the book authors could forget to mention or even intentionally omit the holy grail of productivity – a cross-functional team. First of all, you should not mix team topology and team property. Being cross-functional characterizes a team as self-sufficient in most activities it needs to perform. For example, a platform team is highly likely to be cross-functional to effectively provide the service for its customers. All other team topologies can also acquire the cross-functional property. However, that property describes team internals and not its external behavior. Also, it does not mean that such a team will automatically start executing multiple functions towards the rest of the organization.

From my experience, the truly cross-functional teams are still rare in most organizations due to the DevOps methodology’s misconception and the tendency to reduce it to just one more function or role in existing function-based org charts. When a company uses the ‘DevOps team/department’ or ‘DevOps engineer’ terms in its organizational structure, it’s a warning sign for everyone who really understands what DevOps is about.

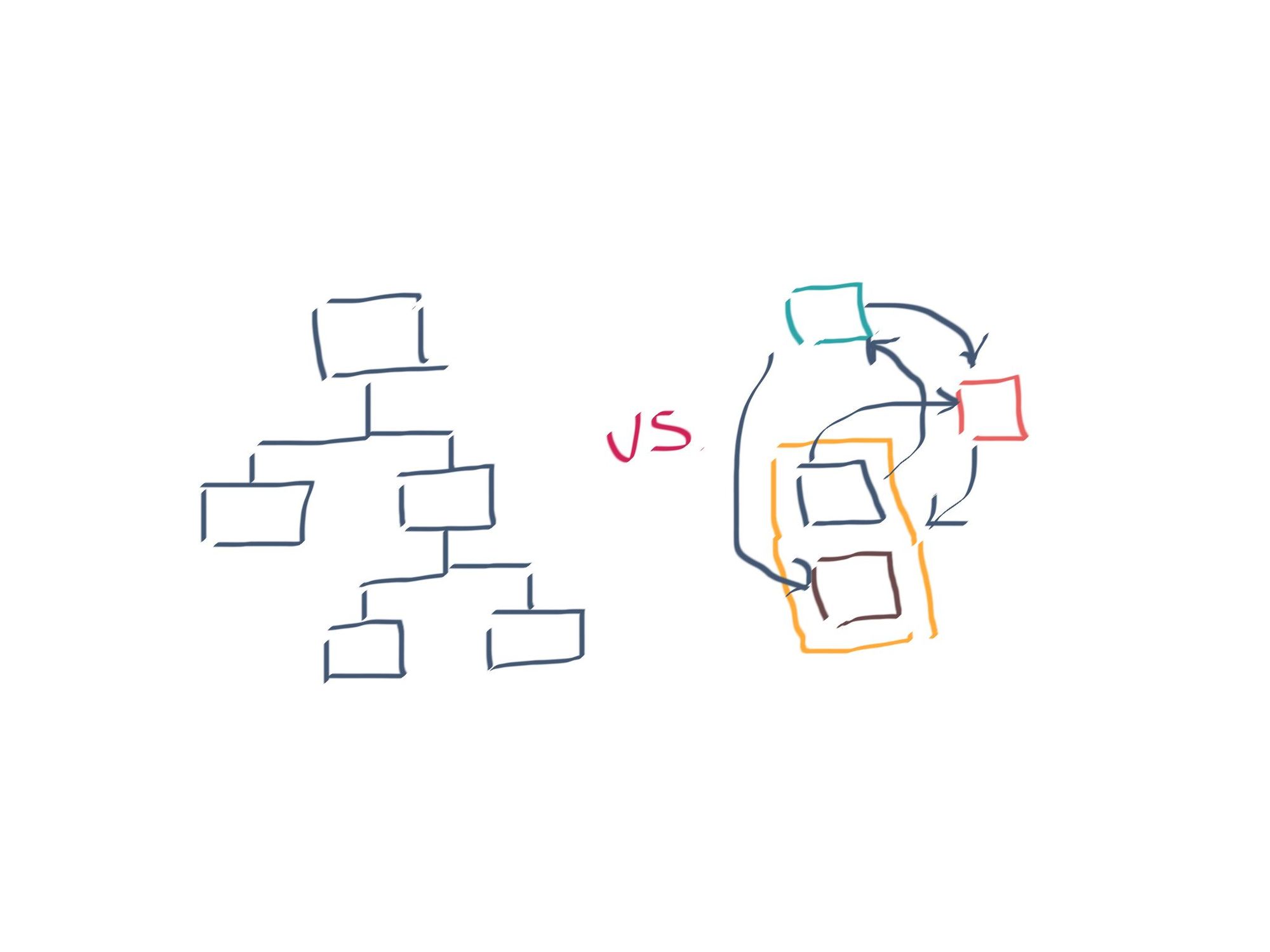

Org charts vs. reality

When I was listening to the book’s final chapters, I couldn’t stop thinking about how I can implement the “Team Topology” ideas at my work and why I feel confused about some of them. Although the theory of team patterns as building blocks of organizations looks pretty solid and reasonable, the concept of enforcing specific interaction modes among the teams seems quite questionable for me. Ask yourself: would you like to work for a company that discourages the freedom of interaction with colleagues from other teams or insist on using only allowed communication means? From my experience, people as social beings tend to create their social connections in any organization regardless of some boundaries on fancy org charts. Moreover, informal communication is usually the most effective way of solving work tasks.

Another open question is related to the pace of changes in modern enterprises. The organizational structure based on well-aligned teams with distinct topologies and clear business values is ideal only when designed. Even before an organization starts working according to the new structure, the market can change, the business priorities might shift, and lots of other changes are highly likely to occur. Also, as organizations are unlikely to adjust their structure to new circumstances every few weeks, existing teams will inevitably have to take on new responsibilities deviating from their initial function. Some companies try to address the described issue by creating flexible org structures with dynamic divisions providing resources temporary for short-term projects, or on an ad-hoc basis. Despite such an approach being useful in some industries, it has lots of limitations and cannot be considered a universal solution. For instance, it is almost impossible to ensure small long-living teams in a matrix organizational structure.

As you might see from those two points, the concept of team topologies is not a magic potion to be consumed without questions. To really benefit from “Team Topologies” in your organization, you should carefully evaluate each topology’s pros and cons before trying it in your specific context. Organizational performance is not achievable through blind obedience to some methodology, but it is improved by deliberate learning of what works for you as each organization is different in its unique way.

Member discussion: